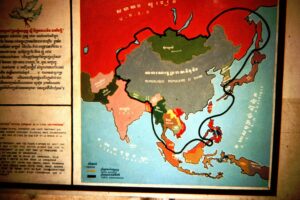

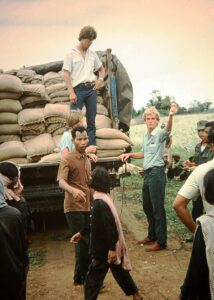

The Landbridge – March thru June 1980 – 20,000 refugees per day. 800,000 sacks of grain crossed the border in 100 days.

Cambodia was not on our agenda. Leona and I were visiting the scattered refugee camps throughout Southeast Asia that resulted from the event we know as the “Boat People of Vietnam”. An estimated one million plus departed Vietnam in overloaded boats primarily between 1976 and 1979 and ended up in refugee camps scattered across the region. It is estimated that up to one third never survived the journey.

Southeast Asia was experiencing multiple crisis in the aftermath of the Vietnam war. We had volunteered with MCC to go to Thailand to assist with the overlapping crisis of the boat people, the convulsions following the Vietnam attack on the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia at Christmas of 1978 and the various refugee groups originating in Laos and Burma. Regrettably the MCC staff on the ground in Bangkok were politically damaged by the experience of Vietnam and were not open to our (potentially more activist) participation.

Since I had already resigned from my role in the family business we accepted an invitation from World Relief, an agency we had worked with in Bangladesh. They wanted to study the situation of unaccompanied minors – children under the age of 16 – who were stranded in these various boat people concentrations. We started in Hong Kong and Bangkok was to be the end of the study.

The study was successful but our conclusions were unexpected. We noted that this was four years into the boat people “event” and the world had been activated by this time. In Canada the private sponsorship program was being launched. A number of developed Western countries together with humanitarian agencies were active in the camps. We realized that a number of them were focused on or at least included the unaccompanied minor situation in their programs. We assessed that the capacity to deal with these children fully matched the scale of the problem and reported to World Relief that we did not recommend their entry into this particular problem.

We found ourselves in Bangkok shortly before Christmas of 1979. One of our contacts was Reg Reimer, the Director of the American agency World Relief – representing the Evangelical churches of America as well as representing the agency of his own church. Reg had been a missionary in Vietnam for many years and had relocated to Bangkok when Vietnam collapsed. Reg and Donna had become engaged in the many facets of humanitarian work that emerged. The following day was a Sunday when meetings with agencies in Bangkok were not possible. Reg suggested that we use the day to visit the Thai-Cambodia border where a large refugee population was trapped.

Reg had been involved in earlier months when the most dramatic part of that crisis had occurred. Vietnam had attacked the Khmer Rouge on Christmas Day of 1978 and Phnom Penh collapsed in weeks. However, as the Khmer Rouge retreated to the jungle they were difficult to defeat. They also enjoyed support from Thailand which was not enthusiastic about Vietnam at its border. Unfortunately (from our perspective) the US Government also assisted the Khmer Rouge in this situation. The US together with a number of Western Governments in fact recognized the Khmer Rouge as the official government for another eight years rather than give credit to Vietnam for destroying these monsters. This political situation of non-recognition was the backdrop for the program we would later develop at the border – since as private actors we could do unofficially what was not possible officially.

It was a beautiful sunny Sunday that was in total contradiction to the reality of the disaster at the border. Between the weakness of the Khmer Rouge and the human disaster of famine, hundreds of thousands of desperate people had emerged from the jungle starting in September of 1979. Many died in the jungle and others in the 2 emergency camps set up to host them. After an estimated 300,000 refugees had filled the camps, the Government of Thailand came to the conclusion that the numbers could become much larger and that the Western Governments who were absorbing the boat people did not have the capacity or willingness to absorb another equally large number. So Thailand sealed the border.

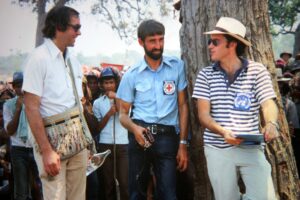

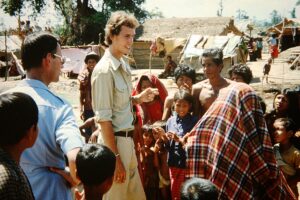

We visited the two refugee camps that hosted the initial influx – Sakeo and Khao-I-Dang, and then went to the border. We met Robert Ashe, an amazing young Brit of 26 years who was in charge of the border distribution. Ashe was married to a Cambodian woman and could speak the language. Technically he was working for a small Christian Agency based in the UK but had assumed a second responsibility as the person in charge of distribution at the border of humanitarian supplies to the rapidly growing number of refugees trapped by the political situation. There was no organized distribution on a Sunday so Ashe could take us on a tour of the vast informal settlement that was estimated at one point to have reached a million persons.

The border ‘refugee city’ was named after the nearby village of Nong Chan. The International Agencies were not able to host this population in camps within Thailand and it was considered unsafe to attempt to build camps inside Cambodia – so this was the situation. The agency that was in charge of providing humanitarian assistance was the ICRC who traditionally show up in these difficult international situations. The ICRC is typically quite strict about using only Swiss nationals in senior positions so it was very unusual to appoint Robert Ashe, age 26 and British, as head of the ICRC for this program. My understanding was that this humanitarian problem developed very quickly and there was a need for immediate response. Ashe was available, willing, had language and skills – we were told he had been made an ’honorary Swiss’!

Ashe was genial and informative but also creative. Although the ICRC was in control or in charge of the distribution process inside Cambodia, the supplies came from a UNICEF warehouse and supply chain located a few miles away inside Thailand. The political consequences of non-recognition of the reality of Vietnamese effective control of Cambodia resulted in strange limitations around the program. The recognition of nations is done by nations and not by the UN or its agencies. For this reason the UN was required to work within the meaning of those rules. The UN was able to distribute ‘humanitarian aid’ to the people trapped in the jungle but since they were located in another (non-recognized) country could not distribute ‘development aid’ which in this case meant supplies like seeds or tools that could be used for an economic purpose. Rice was distributed for food – but it must be hulled so that it could not be planted – a truly bizarre reality!

Ashe wore two hats – that of the ICRC but also his own agency. He took the opportunity to use days like Sunday when there was no official distribution to (literally change his uniform!) and carry out some small programs under the umbrella of his British charity.

On our return to Bangkok we realized that there was an opportunity for service in relationship to the dramatic events at the border of Cambodia and inside Cambodia. Leona and I did not have any plans to apply for or search for an assignment but this situation developed at an opportune moment for us. We had finished the boat people report and were returning to Canada without an agenda.

Reg Reimer in the form of his US agency was interested in getting staff into Cambodia, specifically Phnom Penh if it could be done. We returned to Canada and based on this invitation returned to Bangkok in March with the expectation that I would be able to work inside Cambodia.

The primary international staff in Phnom Penh were from the ICRC and it happened that the senior person in charge was a colleague that I had collaborated with during our time in Bangladesh some 6 years earlier. He was aware of my prior work in Bangladesh with the Bihari refugees and was anxious for me to join him in Phnom Penh.

The access to Phnom Penh was via humanitarian flights operated by the ICRC. Permission to enter would however need to be granted by the Vietnamese officials who were in control. The agency that coordinated NGO’s in Bangkok was asked to write the letter explaining who I was and my purpose. This letter would be presented inside Cambodia and it was expected would lead to a visit where I could negotiate permanent access. The agency writing the letter made a critical error. They used the slightly incorrect name of the Cambodian Government ostensibly in charge – the name they used actually referred to the Khmer Rouge! As can be expected this killed my opportunity to come to Phnom Penh.

We were a little bewildered by the turn of events. We had returned as a family with our two daughters aged 9 and 11 expecting to live in Bangkok for an undetermined period of time. While waiting for a reply from the Vietnamese I made another trip to the border. The humanitarian program was continuing at a large scale but the refugee population could not realistically return to their villages. There was no access to seed and other requirements to begin village life again. March was the beginning of the rainy season and the window for planting rice would be from late March until possibly late June or 3 months.

Prior to my March visit Robert Ashe had carried out an experiment under the umbrella of “Christian Outreach”, his UK agency. They brought a shipment of 10 tons of rice seed to the distribution area and offered it to selected farmers who would test Vietnamese policy by attempting to take into the jungle and through Vietnamese military lines. The Vietnamese did not interfere and allowed the seed rice to pass indicating that they would not have an objection to supply Cambodia through the border.

This may sound like a reasonable and obvious policy decision by all parties but anything to do with Cambodia was not that simple! The UN and its agencies were operating a large-scale relief effort into Cambodia in cooperation with Vietnam. This meant getting supplies to Phnom Penh or the major Cambodia port now controlled by Vietnam – and then presumably the Vietnamese authorities would distribute this aid. This program included the essential rice seed.

The UN had access to two large DC10 air freighters, ship capacity and a reported 1,000 trucks somewhere. An obvious pathway was crossing the border by truck near Nong Chan, but for whatever reason this path was not functioning. A great deal of aid was delivered to Phnom Penh but very little actually reached the villages. The understanding we had was that Vietnamese authorities were only willing to distribute to persons they trusted and presumably who supported the Vietnamese. However, they did not have a system to manage these internal restrictions. The rice seed and other critical supplies were locked in warehouses and very little reached the villages during this critical planting season.

My understanding was that the relationship inside Cambodia was the first official program of its kind between the UN and a Communist Government anywhere. The UN was either protective of this relationship or feared that it could be jeopardized by “unofficial” programs such as the border that bypassed the control of the Vietnamese. This was the backdrop to the discussion that took place after the successful rice seed test by Robert Ashe.

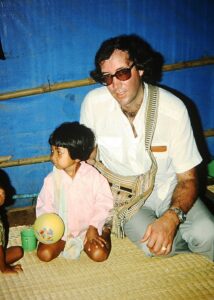

Cambodian faces – Life must go on

Given my inability to work from Phnom Penh and the fact that family was in Bangkok – I considered alternatives. Ashe could assist in creating the conditions at the border that would allow for a much larger rice seed distribution program but as the executive in charge of ICRC could not do this under his own umbrella. I returned to Bangkok and together with Reg Reimer quickly worked out a much larger seed test using US$250,000 available from World Relief. Our little team was quickly expanded with the addition of Bill Barclay an American who had been working on aid programs inside Thailand and had a very helpful Agricultural background and local expertise. Gary Johnson had a missionary background, spoke the language and was already working with related agencies in the refugee camps.

An additional and essential partner was the Bangkok Trading company Suisindo. It was owned and operated by Yvette Pierpaoli and her Swiss partner. Yvette, according to her own story arrived as an orphan from Paris on a one-way ticket in her teens. I noted with interest that her backstory in Wikipedia is quite different. The persons who appear to have offered those facts were connected to the CIA – and specifically deny that she was associated with the CIA as had been widely reported!

Yvette had lived in Phnom Penh and operated a trading firm that included close relationships with North Korea. She had a close friendship with John Le Carre’ and some of his spy novels have stories about Southeast Asia that could well have been spiced with her insights. Following her death on a road trip into Kosovo during that war – Le Carre’ dedicated his book “The Constant Gardener” to her.

In any event Yvette was an essential partner in the Landbridge. She employed a number of young Chinese women – the majority of Bangkok residents are in fact Chinese although their names are Thai by law – and I developed a life-long appreciation for the intelligence and capacity of that group. This was 1980 – well before the arrival of the mobile phone and its incredible ability to facilitate communication. My World Relief office and residence was in the suburbs and this pre-dated some of the marvelous urban highways that have been built in Bangkok. I would work in the office with my very competent assistant Donna from sunrise until offices would open in the City Center. I had a driver named Leng who had a quality car with far too much air-conditioning. He spoke no English and I spoke no Thai but we managed amazingly well. The land-based phones would work so I could start my morning by phoning offices as they opened and arrange for appointments, messages, pickups or deliveries. Leng and I then headed into the busy traffic of the downtown on a carefully planned circular path. When I had an appointment that required some time, Leng would depart to make a delivery to another location or make a pickup of documents or whatever.

Everyone was aware of the urgency of events at the Landbridge border and would accommodate any request for an urgent meeting or a quick response. My pattern was a very regular series of visits to the border – 4 hours by car – and then back to Bangkok so we could deal with both ends of the program in person. Bill Barclay and Gary Johnson were based primarily at the border, Reg Reimer was in the office in Bangkok to deal with agencies and our donors – and I managed the facilitation at both ends.

The Suisindo office under the very active direction of Yvette would manage the international sourcing, purchasing, transportation, packaging and whatever else was required to make the very large and diverse program work.

ICRC controlled the actual distribution on the border and Robert Ashe would manage most of that relationship. The other important aspect was the ability to accumulate and warehouse our products near the border and to arrange for loading and shipping to the border at the appropriate time. The requirements were typically 40 over-loaded trucks 3 times each week. UNICEF had a warehouse near Nong Chan and was in charge of this process for all of the humanitarian aid and was very willing and competent in handling our program as well – regardless of the turbulence at the various headquarters around the world!

The Landbridge Program

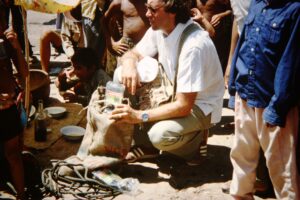

World Relief offered an initial allocation of US$250,000 in mid-March of 1980 which we used to purchase rice seed. Under the direction primarily of Bill Barclay we researched the requirements for different rice varieties and characteristics such as depth of water that would be appropriate for Cambodia. The weight of bags was designed based on what a typical probably under-nourished Cambodian person could carry for potentially long distances. Each bag would contain printed instructions – but more important, the outside of the sack had a picture of a person showing the height of rice next to that image. The growing conditions in Cambodia range from upland rice where minimal height of the stalk is preferable all the way to what is referred to as ‘floating rice’ which is grown on and around the large seasonal lake Tonle Sap which rises and falls with the monsoon. The rice is planted on dry land and grows as the annual flood raises the height of the lake by up to 20 feet.

The initial purchase of seed was successfully distributed at Nong Chan in late March and by all reports was very successful in terms of navigating the Vietnamese military. We had expressions of interest from other agencies with funding but not willing or able to launch their own programs. I returned to Bangkok immediately after the distribution and invited a number of such agencies and donors to a meeting where we presented the results of the distribution and explained the system. There was great interest and 7 different agencies volunteered to donate US$250,000 each if they could take credit for the seed already distributed. We accepted all of their offers with plans to immediately use all of those funds to purchase additional seed and plan a regular pattern of distribution.

The only agency that had independent funding and the capability of operating a distribution program – using the same border system run by Robert Ashe – was CARE. We coordinated our distribution on alternate days and the two agencies operated as a seamless program from the perspective of the refugees and the authorities at the border.

We were distributing rice seed at a high rate and both agencies were running out of funding. Although the UN agencies could not themselves distribute rice seed there was a great deal of interest and support. WFP – World Food Program – would be a natural source of funding or supply for such a program. They had received US$2,000,000 in funding from USAID for the purpose of supporting the re-building of Cambodia but did not themselves have the capability or possibly the authority to operate their own program. As a result they offered the funds to both World Relief and CARE to amplify or continue their programs.

Both agencies were competent and both maintained good relationships with the UN system. As a result, WFP and UNICEF made the decision that both agencies should apply – presumably with the idea that they would divide the funding. There was only one condition. The success and volume of our program at the border was beginning to create tension with the Headquarters of several UN agencies who were protective of their relationships with Vietnam in Phnom Penh. As stated earlier – they were not achieving the desired distribution results inside Cambodia. At the highest levels there was a feeling that this (additional distribution with a UN funding connection) would have a negative effect on the relationships between the UN and Vietnam. The request and presumably a condition of the funding was that we should restrain our rate of delivery to some more politically (for the UN ) acceptable level. Their proposal was to reduce the rate of delivery by as much as 75%!

This matter was discussed with CARE who took the position that their HQ would not approve of them potentially losing a million dollars or greater grant because they would make a point of principle out of that condition – although they fully agreed that the higher rate of distribution represented the capacity of the refugees to absorb and was certainly needed inside Cambodia. We came to an interesting understanding: Both agencies would apply for US$1,000,000 and CARE would state that they accepted the conditions but World Relief would not accept an artificial limitation on distribution. WFP and UNICEF then had the choice of giving all of the funds to CARE with conditions or relieving both of us of that condition. The UN agencies did not want their artificial restriction of aid distribution to become public and possibly hit the news so this created a dilemma for them.

This resulted in some interesting and high stakes drama! The setting was UNICEF HQ in Bangkok chaired by Roland Christianson – the highly esteemed local head of UNICEF. A large number of UN officials from various agencies sat on both sides of a long table with Christianson in the center – and opposite him was his fiery red-headed deputy from Ireland. It happened that I had prior experience with the deputy when MCC set up a large program in the Bihari camp in Saidpur, Bangladesh and he was part of an Irish agency concern in that same location. His reaction at the event suggested some prior memory or grudge that I had no knowledge of.

CARE and World Relief in the persons of myself and the local head of CARE were given two seats at the end of the table. We were each expected to make our formal request – the understanding was that we would each ask for US$1,000,000 and the agencies around the table would come to a conclusion. Although CARE and World Relief had an explicit agreement that we would each ask for US$1,000,000, CARE surprised everyone by asking for the full US$2,000,000. I then formulated my request as agreed for the US$1,000,000 but was explicit in stating that I would not accept the condition of restricting the rate of distribution – whereas CARE was clear that they would accept that condition.

There was a shocked silence since all parties understood the implications. Then the fiery deputy leaned forward, looked to the end of the table where I was sitting and said loudly “Then Screw World Relief!”. The blue-eyed Dane who headed UNICEF and was a model of integrity leaned forward across the table while the red-haired Irish deputy retreated and looked for a place to escape. After what seemed like a very long silence Christianson turned to our end of the table and stated simply “Both CARE and World Relief will each receive US$1,000,000. The meeting is adjourned.”

As we left the meeting the head of CARE turned to me and said, “I apologize – but if it comes to principle or money – my HQ will always take the money!”

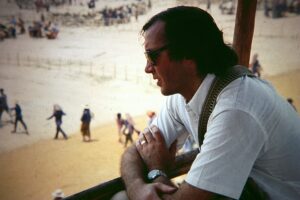

There would be a sequel to this story. Yvette Pierpaoli, Joan Baez plus myself and my partner in World Relief would go to Geneva to attempt to influence a UN Conference on precisely the question of rate of distribution. Yvette invited her friend the British author on books about Cambodia, William Shawcross, to participate.

A number of years later when I had long returned to Canada and the Landbridge was history, Shawcross would return to the region and write a book titled “Quality of Mercy”. In that book he tells the story of the Landbridge and the rice seed project. From information I received he interviewed a number of individuals and agencies including CARE – the same people were still present but nobody from World Relief. The thesis of the story in that book focuses on the leadership role of CARE in the border program and suggests that I was a tool of the American Government.

I expect the leader of CARE would have been embarrassed to have the real story printed! He told his story – here is mine!

The Landbridge would continue with a great deal of momentum and success. In early May there was renewed pressure to slow the rate of distribution. A memorable incident was a phone call from the UN to attend to a group of leaders late one night at the historic Erewan Hotel in Bangkok. It was near midnight and I was confronted by the head of UNICEF from New York, the head of ICRC from Geneva and Sir Robert Jackson the overall head of UN Coordination regarding all issues about Cambodia. There was no air-conditioning and Jackson was sweating without a shirt covering his ample body. The other executives were dressed for travel, suitcases by their side, on the way to the airport for a return to Europe. They wanted me to agree to slow down our program – it was an amazing spectacle when you consider the power and authority of this group. I acknowledged their concern but reminded them that I supplied the rice seed and other products but the system required the full logistic cooperation of UNICEF and the administrative management of the border operated by ICRC. These agencies could simply not distribute our products or distribute at a lesser rate – they had the power to do so. The trio departed with significant frustration.

By this time CARE had run out of funding so it was really a World Relief event at the Landbridge. We would ship 40 trucks of rice seed 3 days per week plus whatever additional products, such as tools or other useful recovery products were available.

Robert Ashe and the UN Agencies had developed an interesting and effective system. The distribution process was designed to register and distribute in a controlled manner to 21,000 persons each day. As the rice seed became available the system was re-organized so that, for example, 21,000 persons would be registered for a Monday distribution and the system would allow the same 21,000 to return on Tuesday to receive all of the products that we could distribute but were outside of the range possible by the UN. The 21,000 persons were organized in groups of 30. Ashe had designed a system where it was difficult for persons to abuse the system. The group of 30 were identified and if they were arriving with a group less than 30 – often to capture more aid – then they would receive nothing if there was not a minimal identifiable minimum such as 25.

All refugees required and could benefit from the food products distributed by the UN, but it was clear that the needs in terms of seed, tools or fishing nets were much more variable. Our group had devised a simple answer to that problem. All refugees were encouraged to come through on the second day and accept whatever was offered. If for example a widow with children could use more food but could not herself use the rice seed or tools, we encouraged a market system where they could exchange what they did not need themselves for products such as food that they could use. We learned from interviews of refugees that there were assembly points and markets just beyond the Vietnam military lines. Refugees quickly developed more formal markets which allowed them to take whatever was distributed. For example, a farmer who needed rice at a height of 2 meters but received a rice that was much shorter could make that exchange. Our World Relief staff had gone to great length to research the approximate mix of rice varieties and characteristic required inside Cambodia and arranged a mix that approximated this demand. From all reports this informal system worked very effectively.

The Landbridge in Crisis

The UN responded to my meeting with the UN officials by instructing Robert Ashe to only distribute 10 trucks per day rather than the typical 40. What we found interesting is that the UNICEF warehouse at the border did not themselves restrict the loading and shipping to 10 trucks! Clearly there were some dynamics taking place within the larger system.

This represented a new challenge. The setting was agricultural land on the Thai side and jungle as you crossed the border into Cambodia. The distribution point was approximately one kilometer inside Cambodia. We made a quick decision and instructed UNICEF to ship all 40 trucks but at the border only 10 were allowed to enter Cambodia. The road was a relatively primitive earth road. The 30 trucks that could not cross lined up at the edge of the road just inside Thailand. We paid the drivers a substantial premium to encourage them to accept the risk of staying with their trucks in the middle of nowhere. Day 3 another 40 trucks arrived and 10 crossed the border. After day 5 there were 90 trucks parked along the border in a line that made quite a statement considering the setting!

The war correspondents cruising the border zone noticed this unusual situation and began to ask questions. The local UN officials told them to go to Bangkok and speak to Art DeFehr. The first correspondent to show up was from Newsweek. I offered to provide the story with some degree of protection of my identity.

The Newsweek journalist agreed to the terms and I showed him all of the emails. The next day he published a full-page article titled “Seeds of Famine”. I received an urgent call to UN HQ – where the trembling senior official showed me a copy of the article all marked up with a highlighter. There were six Quotes of ‘different’ individuals – all of them actually happened to be me but I was given a different title relative to each quote. He was quite certain where the information had come from and let loose with an expletive realizing he could not do anything. In any event the next day the border opened to our traffic and it resumed – until the next crisis!

There would in fact be two more crisis in this amazingly short period of time. One revolved around the nature of items we were supplying to the refugees. In this situation I called a friend at the Far East Economic Review published in Singapore and he put out our story – again it was resolved within hours!!

By this time the Landbridge and border re-supply program had became both varied and sophisticated. Many Cambodians have access to water and fishing whether it is the very large Tonle Sap or various ponds and rivers. There was an absence of adequate nets and material for fishing nets after years of disruption. We did a study and determined that if we supplied the yarn the Cambodians could create nets on their own – each designed for the particular circumstances where they were fishing – so a huge amount of fishing net material crossed the border.

Bill Barclay studied the question of tools to re-create the items needed in a village for agriculture and transport. We decided that the cart with large wheels pulled by oxen was ubiquitous and was also the most complicated item used in a village. We developed a set of only 6 (metal) tools such as a saw blade but not the full saw, a chisel head without the handle and so forth – leaving out all of the parts that they could reproduce with the tools we sent. This allowed for a smaller package and a much higher quantity – we correspondingly shipped tens of thousands of kits using this approach. The curved blade essential for harvesting the rice became a controversial item when one of the UN agencies complained that these could be used as weapons!

Another item that was included in our program was packages of vegetable seeds. I had earlier been part of a program in Bangladesh where we developed a package of popular vegetable seeds that were packaged in small individual packages for a Village and then as a group of 6 or 7 critical and valuable vegetable seeds would be packaged inside an aluminum foil package to preserve their germination. The packages were provided with written but also visual instructions so that a non-literate person could correctly use the seeds. We distributed hundreds of thousands of these packages. Yvette and her amazing crew purchased the seed from around the world ( in days not months!) set up a circus tent in Bangkok and in a matter of a few days (and nights) created all of these packages. The instructions to the designers of the packages were: “If the package was dropped from an airplane into a village they should be able to use the seeds correctly.”

The Challenge of the Geneva Conference

The story of the Conference and our role is described in more detail in a blog and essay titled “Weekend in Geneva“.

The UN organized a large Conference for officials at the level of Ministers of Foreign Affairs in Geneva in late May of 1980. I received a call from the Canadian Embassy in Bangkok on a Thursday prior to the Monday conference. They advised that the organizers of the Conference – the UN – had not provided an agenda or any advance information as to the outcome they expected from the event. This made Governments nervous since they were sending the top International Affairs person from each country with very little advance notice as to the agenda. In our case there was concern that the UN wanted to control the agenda as to how to deal with Cambodia – in our case this meant focusing all or most of the authority and aid through their programs in Phnom Penh in cooperation with Vietnam.

I was asked to write a paper as to what was happening at the border in terms of humanitarian and economic assistance and my perspective as to what a reduction in that program would mean. I worked all of Thursday night – in the absence of modern equipment and together with my amazing assistant Donna produced a paper titled “Seeds of Famine.” We had no Xerox machine so the document was typed a number of times with carbon paper.

There was a meeting of 10 Western nations at the Canadian Embassy on Friday morning and my paper was distributed – and I understand it was forwarded to each of their countries as advance information for the Geneva event. Someone suggested it was possibly the only paper read by their senior representative to the conference in advance and therefore possibly had an outsized influence.

We realized that our Landbridge program might be in jeopardy so made the very quick decision to travel to Geneva and make our case in whatever way possible. Yvette Pierpaoli was willing and quickly organized two additional persons. One was her friend, Joan Baez the singer with a cause from the US, and William Shawcross from the UK who had written the major books on Cambodia. We arrived on Sunday morning and quickly got organized. Joan Baez had a large suite in a lakeside hotel and we invited the Ambassadors of the countries who had received my paper to a private Sunday evening reception – they were more than willing to attend and Baez had written a couple of songs especially for the occasion! This allowed opportunity for me to speak with a number of them and explain our situation.

As the Geneva event progressed on Monday morning we noted that a paper was being distributed to each delegation – and from a distance I could tell from the layout that it was my paper. Presumably there was some awareness that there was another flow of information that had influenced the attitude of a number of major countries and there was curiosity as to the source of the alternate information.

Monday morning our group of 5 were the sole occupants of the visitors balcony. The countries presented in alphabetical order so we could easily keep score. We listened carefully as each of the 10 countries with whom we had communicated made their presentations. All of them used language that reflected our position with the exception of Switzerland. They were presumably protective of the ICRC – their agency in this situation. After number six we were approached in the balcony and asked to come to the lobby to meet the Head of the Global Red Cross Societies. He was very upset and simply asked – “What the Hell do You want?” We suggested that we were simply concerned that Aid policy was being set based on the reputational concerns of UN agencies rather than the impact on the refugees and wanted the UN to allow the border program to proceed at the pace equivalent to what the refugees could responsibly absorb.

We never learned whether the language of the resolutions was changed but the outcome was that we were left to proceed in peace at the border.

Khmer Rouge Return to the Jungle and the Fight

The UNHCR was also engaged in the situation but not at the border. They managed the Khao–I-Dang and Sakeo refugee camps inside Thailand. The Sakeo camp was the first to be established during the Autumn of 1979 emergency and included a high percentage of Khmer Rouge fighters and their families or at least sympathizers. It was assumed that the Khmer Rouge within the camp were effectively in control.

In June of 1980 the UNHCR in its wisdom responded to the request of a number of those in the camp to return to Cambodia. By return they meant that they were now healthy and wanted to re-join the fight against the Vietnamese. This may sound counter-intuitive but as mentioned earlier, the US and several other Western countries together with Thailand and China were supporting (or at least recognizing) the Khmer Rouge officially rather than the Vietnamese.

The fighters wanted their families including children to return with them. World Relief and other agencies were involved inside the camps offering health services and were aware of the politics in play. Since agencies associated with World Relief included a number of mission societies that had earlier been active inside Cambodia, they had access to quality speakers of the language and familiarity with the culture. We were quietly approached by camp residents who informed us that many of them would be under pressure to leave with the fighters whatever their personal wishes.

The UNHCR was made aware and did not themselves have the capacity to deal culturally with this situation. When the time for departure arrived they developed a process where those who desired to leave would individually move through a series of tents where they would be interviewed. Since the UN could not deal with the cultural challenges they permitted a second stage where each person was required to go privately through another tent where they were interviewed by our Khmer speakers – persons whom the refugees were more likely to trust. The Khmer Rouge had developed a system of taking the young children of families and attaching a child to a family that was genuinely willing to return to the jungle. When the real parent came through the process an hour to two later they were faced with the dilemma of joining the departure or losing their child. We were able to create on opportunity for such a parent to tell the truth and we would then retrieve the children who were in the departing group but had not yet departed and allow the family to be reunited and to remain in the camp. We saved a number of families from such a forced return to the jungle but we certainly will have missed some in this impossible situation.

The fighters and families who survived this process were placed on buses and taken across the border into the jungle. I was able to follow the group of buses together with a dozen cars full of international journalists. We stopped inside Cambodia on a lonely dirt road. The fighters, often including the women, were carrying large cloth ‘sausages’ around their necks filled with food – presumably rice – ready to return to the battle. As the doors of the buses opened a number of Khmer Rouge fighters emerged from the tall grass all around us to welcome their friends. The world press were all over the event and we simply watched and marveled.

Zia’s Little War

Thailand was a very active place that year. A global evangelical conference was taking place at the Pattaya Beach Resort that same week. I had been asked to arrange for a visit to the Landbridge for some of the international delegates. The tour took place immediately after the return of the Khmer Rouge. We had arranged for several buses to take those who were interested to visit the Nong Chan distribution point. As we approached the border I realized that I was taking several busloads of international delegates into a no-man’s land that was really in a state of war. We stopped the buses just inside Thailand and I explained the situation and the risk over the speakers. Only one person decided to leave the bus – a delegate with a personal history from Vietnam. He simply said it did not smell right. The rest of us completed the visit and returned to Pattaya.

Very early the next morning I was contacted in Pattaya to advise that the Vietnamese had staged an attack across the border, specifically at our Nong Chan distribution point. After a 4-hour drive I was back near the border by noon. The Vietnamese had attacked several very local Thai border fortifications and in the end we were aware of about 80 recorded casualties.

The Vietnamese and the Thais were shelling each other at a distance of 18 km. We joined a group of men with plenty of communications equipment. They were the non-disguised local members of the CIA. We knew them as employees of the US Government but in this situation they dropped all pretenses. My first concern was the safety of my two expatriate staff who managed our border operations. I had checked their residence on the way and they and their vehicle were not in sight. The CIA agents were fully aware of my staff and advised that they had made a number of rescue or “ambulance” runs into the zone between the two armies to rescue injured refugees who were trapped. The UN, ICRC and several other agencies were present and visible but they all remained beyond the range of the Vietnamese shelling based on orders from their superiors. My staff had made their own decisions even before Reg Reimer or myself were aware of the problem. They had simply decided that they would take the personal risk and rescue injured refugees – and had already made a number of trips.

The CIA seemed to have some ability to track events and informed me that our group was static in one location within a km of the Vietnamese guns. When there was a lull in the shelling I decided to drive to that location. They were hiding in a cluster of palm trees. A Vietnamese soldier had appeared – crawling through the tall grass – and wanted to defect. He was now in the back seat of their vehicle and this presented a problem. The response of the Thai soldiers on our return could be unpredictable – given that they had lost a number of their own soldiers.

A Thai gunship passed overhead at a relatively low altitude and was directing its fire at the treeline across the rice paddies – presumably where the Vietnamese guns were located. As we watched, the helicopter was hit by the Vietnamese, exploded and came down in pieces. The Thais sent a spotter plane presumably to identify the location of the guns – and was itself hit and fell into the field in front of us. That elicited an angry response from the Thais and for the next several hours there was intense artillery fire in both directions. We were aware that the Thais were firing at 18 km and the target was less than a km beyond us. We were hoping that they had the capability of being accurate!

When the rate of shelling decreased we decided to drive to safety. Along the way we passed large groups of refugees who had been stranded in the middle of the fighting. In many cases they had dug small trenches where they were sheltering with their families.

At one point we passed a small earth fortification built by the Thais and now abandoned. On the approach to this fortification there were 11 Vietnamese bodies strewn around the area. We stopped to take photos. A Thai interpreter immediately warned us to stay clear of the bodies – he suggested that the unnatural way they had been placed suggested some sense of purpose and likely they were booby-trapped.

I returned to the Pattaya Conference. The active fighting had stopped so Robert Ashe and a UN medical officer decided to visit the Nong Chan distribution point to determine if it would be possible to resume the program. The camp appeared totally abandoned but as they approached on foot they were confronted by an armed Vietnamese soldier who stepped out of the forest. They were captured and disappeared for 3 days – this made world news. On the third day they suddenly emerged at another point on the border – presumably all of the world attention did not make them prisoners of sufficient value to Vietnam. As Robert Ashe left a large news conference in Bangkok he turned to me and said “You would have loved the experience!”. They were well treated so it became an adventure!

The program to repatriate active and healthy Khmer Rouge to resume fighting had been controversial. The senior person in UNHCR who authorized this program was Zia Rizvi. As a result, within the UNHCR this whole debacle was always remembered as “Zia’s Little War!”.

After this border violence a calm was restored and the UN continued its humanitarian program. By this time we had been distributing very large amounts of rice seed for 3 months and this had encouraged many refugees to leave the border to return to their villages. The objective of the Landbridge and the distribution of rice seed was to enable the Cambodians to return to their land and villages and survive. The rains were increasing which signaled the beginning of the planting period. We determined that we had accomplished as much as was possible in terms of a restoration of village life and announced the end of the Landbridge.

In a period of 100 days we had distributed 800,000 sacks of rice seed, tens of thousands of SAPS – Subsistence Agricultural Packages – that contained the critical tools for planting, ploughing and harvesting plus fishnets, over a hundred thousand packages of vegetable seed and more. We had survived global and local politics, a war, logistic challenges and financial hurdles. The weather and geography had been the least of our problems.

The Politics of the Landbridge

Many years later I would visit a friend at the ICRC HQ in Geneva. He shared with me that he was pleased that I could not read French. He noted that in the years following what had been a very successful border intervention that the ICRC had opposed – they now realized that it had been a great success. Since the technical leadership at the border was Robert Ashe wearing an ICRC uniform – they now took full credit for all of the activities and had written their own report – a report that totally failed to mention our agency and the role we played. He simply stated that he and his colleagues fully understood the reality of that event and would have been embarrassed if we could actually read the report!

The politics and corruption did not ignore the Landbridge. As World Relief began sourcing and purchasing large quantities of rice seed through the offices of Yvette and Suisindo we received a call from an official connected with the WFP. He was actually an American auditor for US AID and the US$2,000,000 described earlier originated with USAID. He attempted to direct our purchase to sources in Thailand that offered rice seed at much higher prices. Since his agency was the origin of the funds it led to some confusion.

It happened that I was personally familiar with the global head of WFP located In Rome. Several years earlier when we established the Canadian Foodgrains Bank he had been the head of the Canadian Wheat Board – and the person with whom we negotiated the structural relationship with the Foodgrains Bank. I sent him a personal telegram describing the situation. He immediately recognized what was going on and instructed us to say nothing but source rice seed from wherever we felt it was the best value. We could not learn the source of purchase by CARE (who shared this source of funding) since we assumed they would experience the same pressure. Based on later events we suspect they did buy the expensive seed!

This story had a sequel! We returned to Canada after travels in Asia. In September I read a story on the front page of the Winnipeg Free Press that the FBI had conducted a sting operation at the Georgetown Inn in Washington DC. A business person from Thailand had arranged to meet an American Government official at this hotel presumably to transfer a large amount of cash as payment for favors done in Thailand. The American was the auditor who had approached us and the Thai person was the business partner of Yvette who was cooperating with the American Government to catch this agent in the act on American soil.

Although I had nothing to do with this event I became inconveniently involved. The Auditor had placed a call to me from the hotel the previous day asking if I had good photographs of the Landbridge operation that I could share with him. I had no reason not to share so I presume this discussion was recorded by the FBI. Fortunately they did not make any effort to enmesh me further in this problem – it is quite possible that they were fully informed of the facts and how we had handled the events.

Cambodia Chapter 2 – Winter of 1981

A number of humanitarian agencies had gained a great deal of credibility and burnished their reputations as a consequence of the Landbridge and related border operations. Many Cambodians had returned from the border to resume village life but there was still a large residual population. Many agencies felt that the Landbridge could be repeated given its success in 1980.

I was invited to return to lead a second effort but had my concerns about the relevance of a repeat operation when conditions on the ground at the border and inside Cambodia had changed so much. I agreed to consider the request but specified that I would first like to visit Phnom Penh to gauge the changed reality and assess the politics of a second rice seed Landbridge.

It was stated by persons in Bangkok that the Vietnamese “hated our guts” and would never invite us for a visit. We persisted and Bill Barclay and I received an invitation within 24 hours of our request – they were clearly very open to meet with us. I took the view that they were rational people and while publicly denouncing our border program, they had done nothing at all to complicate or stop our actions – so that I assumed this was an informal approval of the whole event.

In the absence of anything commercial, the only way to fly would be on an emergency relief flight. We arranged to travel to Singapore where we joined a World Vision flight using a WWII bomber of very questionable quality. The relief supplies were strapped to the floor in the center and we made ourselves comfortable wherever we could – certainly no seat or seatbelts! On what we assumed was arrival we circled an airport where the jungle fringes were loaded with destroyed or abandoned aircraft of all kinds. The World Vision person in charge of the flight and with some familiarity looked out the window and stated – “wherever we are this is not Phnom Penh!” We landed and the pilot rushed back with an explanation. He was stopping in Saigon – now Ho Chi Minh the southern capital of Vietnam to deliver a new American aircraft engine that he had hidden in the tail of the plane. He would accept some antique elephant statues of presumably considerable value in return! The World vision person became quite animated and insisted that with the addition of such a heavy engine the aid shipment must have been less than the agreed amount. The pilot simply said – you have a full load but we arrived empty tanks!

We were treated well by the Vietnamese authorities and managed to buy a few souvenirs! We really did arrive empty tanks and needed some fuel to get up in the air and fly the 130 miles to Phnom Penh. They gave the pilot a few gallons of fuel and we managed to get into the air and more or less glided into a dark Phnom Penh airport at twilight. We landed hard and blew both tires and veered into a rice paddy. There were no lights or activity at the airport and after a little while some lights came down the runway. A landrover arrived to pick us up and suggested we go to dinner first and worry about the plane later!

We arrived in the dark center of Phnom Penh on the large main avenue totally devoid of traffic. Some Cambodians had returned to the city but were camping along the side of the streets rather than use the empty buildings. Two hotels had been activated by the International Agencies- one for sleeping and the other eating!

After dinner our pilot announced he was returning to the airport with a flashlight and would search in the jungle fringes for abandoned aircraft that might have wheels and axles that could fit his now damaged aircraft. He was successful and took off in the morning.

The next day we were received courteously by Vietnamese Government officials. After a little discussion the senior person at the meeting suddenly blurted out – “I know both of you people – I took an oxcart, travelled to the border and disguised as a farmer observed and went through your whole distribution process”. It was an interesting moment! He then went on to observe that he was aware that we were distributing Cambodian bibles to refugees to take back inside Cambodia. Farmers would hide the bibles in the middle of the rice seed sacks to avoid detection and many made it back to villages all over Cambodia. The official then wanted to discount our efforts and stated that the Cambodians who took the bibles did not really want them for their contents. Rather the Bibles were printed on a high quality thin paper and he noted that paper was excellent for rolling cigarettes – and that was the real reason for their acceptance.

We wanted to test their attitude toward a second Landbridge program. They had already announced their objections to such a renewed program. They then told us of their efforts to import rice seed direct from Thailand using ship access but the Government of Thailand had withheld permits. We sensed there was an opportunity for a bargain and tested the idea that if the permits to export were granted would there be a greater willingness to accept a second effort at the border. We reported these conversations to the UN and other relevant authorities on our return. The agencies then announced that they intended to pursue a border program, the Thai Government approved some permits and life continued. We have no idea as to the importance of our discussions, but the world of indirect approvals continued.

The Vietnamese were more than willing to expose us to the prisons and killing field evidence perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge. The sites were very fresh and as they excavated bodies there was still hair and other material that had not yet disappeared.

An interesting visit was to a farming area where life and agriculture was returning. In one village we noted that they were making brass jewelry to be used as bells for animals and other products such as jewelry. The source of the metal was a pile of thousands of spent machine gun bullets that would be melted or pounded into a new purpose.

My reflections on Cambodia and the Landbridge

The engagement at the border of Cambodia was certainly one of the most meaningful activities of my life. It was accidental, short and intense. Since the family had planned to be in Thailand, we also experienced this as a family.

My ability to make quick decisions and actions was facilitated by my prior experience in Bangladesh some 6 year earlier. I was familiar with the issues, with the senior UN agencies and had developed self-confidence about actions and decisions. I was able to act quickly given a non-hierarchical agency structure. Amazingly the whole event started and stopped in 100 days!

It is always appropriate to give credit to a great variety of agencies and persons who made this all happen – but the reality is that the number of key players who were decisive was very small. Robert Ashe of ICRC at the border itself, Ulf Kristofferson of UNICEF who headed the very effective logistic support near the border, Yvette and her amazing crew who pulled everything together, Bill Barclay and Gary Johnson at the border who made it happen and Reg and Donna Reimer back in Bangkok. These were the key players but of course there was important financial support from many places, Embassy support at critical times and many others – but this was an event driven by a relatively small number of motivated, talented and effective individuals who were generally very open to taking risks. There is no real way to measure the impact of the Landbridge but a few observations are useful:

- It was reported that the Western part of Cambodia experienced a surplus harvest in 1980 versus an expected famine.

- One UN official commented that given the scale of the program it may have saved up to 100,000 lives.

I cannot quantify the outcome but know for certain that it made a very big difference to a great many Cambodians and facilitated a quicker return to normal life.

From a personal point of view it would have an unexpected impact. In the spring of 1982 one year after these events, I was contacted by the Canadian Government to invite me to apply to be the Representative (Head of Mission) of the UNHCR program in Somalia – at the time the second largest refugee program in the world. I learned later that Mark Malloch Brown who had been the head of the Sakeo camp during that time had recommended my name to the UNHCR as a candidate. Brown later became #2 at the UN under Kofi Annan and currently is head of the Soros Society. Somalia was very different but an equally intense and meaningful experience.