“It is easy to start a war but hard to end it”

Myanmar is frequently in the news as it struggles to create peace and a nation out of 135 ethnic communities. Even that incredible number leaves out challenging situations like the Rohingyas.

I had the privilege of participating in the Myanmar Peace Process in November 2016 in the form of a 4-day Peace Forum and workship organized by the Center for Development and Ethnic Studies (CDES) of Myanmar and the Parliamentary Center of Canada. The DeFehr Foundation brought the parties together and provided the funding. This was the fourth Peace-building event sponsored by the DeFehr Foundation since 2013.

- Peace Forum platform including myself as presenter.

- The Peace Forum – an afternoon event that included Government, Ethnic Groups, speakers from workshop, Military plus international actors.

- Workshop breakout session. Burmese always participate enthusiastically in working sessions.

- Political Sector workshop with Armed Ethnic Organizations about the concept of Federal Systems of Government.

Myanmar has been at war for more than 50 years. Other conflicts like Columbia, Israel-Palestine, the Kurds, Afghanistan and parts of Africa share the dubious distinction of seemingly endless wars.

Why are some wars so hard to end?

Myanmar gained its independence from Britain in 1948 but its popular leader Aung San was assassinated before he could take office. Aung San had negotiated independence but equally critically a formula for governance in the form of a federal system of Government that had been accepted by its diverse ethnic communities. The successors to Aung San abandoned federalism and Burma struggled to find its way. In 1962 General Ne Win orchestrated a military coup and became President. His group represented the dominant (68%) Burman/Bamar majority and convinced itself that Burma could become an officially Buddhist country with Burmese as the official language and a dominant political center that made little space for its ethnic diversity.

This resulted in a civil war of more than 50 years with catastrophic results. An estimated million died in the conflict, a larger number escaped as refugees and Burma earned the dubious distinction as one of the poorest countries in Asia – in spite of its rich natural endowment. The student revolt of 1988 was a precursor to Tiananmen in 1989 and produced the generation of leaders that are now leading the Peace process. In 2011 a new military leader, Thein Sein, realized that Plan A was not working and announced Plan B – to create space for other political actors in the Government. They were prodded in this direction in large part because each time they attempted to demonstrate their popularity through an election – they were trounced – finally recognizing that even their own ethnic community did not support their nativistic and repressive regime.

History is a grand process but sometimes the unexpected happens in the pivotal role of an individual – and sometimes this individual had never planned to be part of the process. The accidental presence in Myanmar of Aung San Suu Kyi (daughter of Aung San) during the student revolt of 1988 created one of these rare moments that has the power to shape history.

- Dr. Lian Sakhong the Chief Negotiator for the Armed Ethnic groups.

- Aung San Suu Kyi – a very impressive person.

- Art and Leona DeFehr with Aung San Suu Kyi.

- Leona speaking at the workshop.

Aung San Suu Kyi seized the moment and started and led a political process that has dominated every election attempt – in spite of every effort to silence or isolate her. She paid a heavy personal price but has emerged as a strong leader. In 2012 she assumed a role in Government and in spite of a law designed to prevent her leadership has navigated the very difficult political shoals to play a guiding role in the establishment of a participative form of Government. She is frequently criticized for what she has not accomplished or causes she does not support – especially the very complex situation of the Rohingya Muslim minority in Rakhine state. She walks a delicate tightrope as the head of a party representing primarily the Burman majority but attempting to guide a process of inclusion for the ethnic communities and states in open rebellion.

The Peace Process started in 2012 and is expected to take another 4 years. Why so long? There are 16 important armed ethnic groups with various degrees of strength, history and geographic challenges. After 5 decades these groups have effectively become local Government with an embedded political and economic benefit including the drug trade. Signing away their authority is not seen as an automatic benefit to leaders who are established. On the other hand, the military and business associates of the regime have effectively absconded with the wealth of the country through ownership, monopolies or other structures. They similarly do not see the benefit to themselves and their families of participating in a more equitable form of governance.

Within this unstable environment the parties are slowly pushing the process in the direction of Peace, sometimes with a few steps back. 8 of the Armed Ethnic Organizations (AEO) have signed Cease-Fire Agreements while the others have found various reasons to hold out for better terms. (As the reality of loss of political and economic power by the military elite becomes more of a reality the hard-liners in the military are digging in their heels creating the current stalemate). After more than 5 decades of costly conflict all of the parties have convinced themselves of the merit of their cause and hold out for an ideal solution – if an ideal solution existed for all sides there would have been Peace a long time ago. The purpose of the Peace Process and our goal in engagement is to provide opportunity for the actors to more fully understand the compromises required to achieve Peace.

Our first event in partnership with the CDES in 2013 was a one-week seminar which targeted 26 political parties plus a number of the Armed Groups. The program was a seminar on techniques of negotiation – how to talk without becoming antagonistic. One person stated: ”After 50 years we know how to fight but do not know how to talk!” This was followed by two regional events and the recent national event.

- Platform poster for Seminar and workshop re Peacebuilding.

- Zaceu Lian, Head of Council of Democracy and a Canadian who has returned to Myanmar to promote the peace process.

- Workshop posters from Negotiating Seminar. These Burmese are creative and participate enthusiastically.

- Everyone received a Certificate of Achievement. These Buddhist nuns were fully engaged in the process.

After 5 years of process the challenge has moved from negotiation to substance. In this last event (November 2016) we brought experts from Canada to speak about the actual operation of a federal system and the compromises required in areas like power and revenue sharing, how to deal with the unequal distribution of natural resources, how to allocate power between the regional and national levels etc. We are absolutely not the only actors in this process but many Western Governments including Canada have been reluctant to partner with political actors that may technically still be at war. We have taken the position that it is important to participate in the process while it is still fluid and there is room to shape the outcome. Should Peace be achieved there is still plenty of need to assist the new Government – but it is too late to influence the structure of the outcome.

Peace is anything but assured, however there is a fatigue in the nation that creates a climate of hope for Peace.

There are any number of challenges but I will use the example of the Rohingya problem to explain the complexity of issues (see my essay on the Rohingyas in my Blog Post #8 – So..Who are the Rohingyas..and why are they being Persecuted?…July 15, 2015).

The Rohingyas are a Muslim minority in Rakhine State originally from Bengal or now Bangladesh. Many arrived during British times when borders did not exist and as partially a fishing community many continue to be mobile. They share the territory with the ethnic citizens of Rakhine state whose ancestry reaches back to the ancient Empire of Arakan.

The direction of the future political solution/structure in Burma relates territory to ethnicity. Since the Rohingyas are seen as interlopers – any territory assigned to them is a takeaway from another group. We have been told that the Rohingyas have been offered citizenship but as general citizens of Burma and not associated with territory – and their more radical Islamic leaders have ostensibly rejected that outcome.

Whatever the facts it is not difficult to understand the problem and the dilemma for Aung San Suu Kyi as a leader of a party centered in Buddhism and with political support from the Burman majority. That is only one of many challenges in the creation of a new and united Burma!!

Christmas concert in a Christian Church of the Chin ethnic minority in Yangon. The building does not officially exist and the service did not officially take place.

When we look at these seemingly endless conflicts they seem to relate to two principal issues. One is the structure of society that allows for economic domination by a strong person or group. Columbia and arguably the conflict in the DRC relate to economic power. The more intransigent current and recent conflicts relate to identity – whether religious or ethnic. Israel-Palestine, Kurdistan, Timor-Leste, South Sudan, Somalia, the Sunni-Shia divide, Tibet and Myanmar. A conflict between nations can be incredibly vicious and destructive but you can know when there is a victor such as in VietNam. Identity conflicts can be repressed but seldom really end unless there is a political solution and that usually only comes when all parties are exhausted.

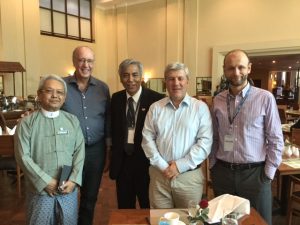

Leaders and speakers at the Peace Forum: Lt. General Khin Zaw Oo ( retired) General Secretary of the Peace Commission, Art DeFehr, Dr. Lian Sakhong (Chief Negotiator), Juan Fernando Londono (Columbia), Ivo Balinov (Parliamentary Center of Canada).

Myanmar has reached that moment and it is critical that they receive the right kind of advice, support and encouragement to move along the path to genuine Peace. We are supporting local leaders in their search for Peace. Our key partner is the Chief negotiator for the Armed Ethnic Groups with a Ph.D in conflict Resolution from Sweden. This small group of courageous Burmese – often survivors of the 1988 student violence – need and deserve the sensitive and generous support of a caring world.

A very interesting intervention and presentation was Juan Fernando Londono of Columbia. He was the key negotiator for the political part of the negotiations between FARC and the Government. The need and the goal (in

Columbia) was to have both sides come to an agreement that respected reality and the aspirations and needs of each group so that they could move to Peace. He explained to the Armed Ethnic Group leaders that Peace is never a one-sided affair and every party must make some kind of compromise. He left us with a very profound thought

Peace has a Price!

This sounds very simple and obvious but in most such negotiations the parties feel that the other group should pay the price – and Londono was very effective in pointing out that Peace is neither free nor easy.

The Burma Peace Forum occurred immediately after the failure of the referendum in Columbia. Londono pointed out that during the four years of negotiation violence had significantly declined and the urban population had come to believe that the problem was gone – and wanted FARC to pay a steep price. The people in the countryside who had been the victims understood that the FARC was still alive in their areas and could return to violence if the talks failed – and were prepared to pay a higher price for peace. The vote followed that perception with the countryside voting in favor of Peace.

The people of Myanmar remain hopeful but there is no guarantee of success.

The following are Myanmar related articles, please click on links below: