This blog is based on a presentation made to the Unitarian-Universalist Fellowship of San Miguel de Allende. The group tends to be from the US East Coast and has a perspective on Mennonites based on their regional experience. Leona and I and friends who occasionally attended the Fellowship did not fit their stereotype.

Has anyone ever said to you – “You do not look like a Unitarian?”

I have often been told that I do not look like a Mennonite – so people have a pre-conceived perception as to what a Mennonite is or believes or should look like.

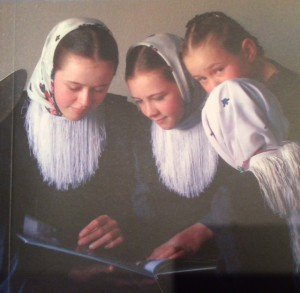

- Mennonite children in rural Mexico – my relatives 8 generations removed

- Mennonites no longer look predictable

- Mennonite musical group look and sound differently around the world

A little reality check….

On a typical Sunday morning Mennonites will worship in approximately 100 countries.

Major cities like Vancouver will host services in a dozen or more languages.

Mennonites will worship in North American mega churches and in remote villages in sub-Saharan Africa.

Meserete Kristos (Mennonite) church in Ethiopia is active in social and rural development

- Meserete Kristos (Mennonite) church in Ethiopia is active in social and rural development

- Meserete Kristos Mennonite congregation in Addis Ababa – church seat 3,000

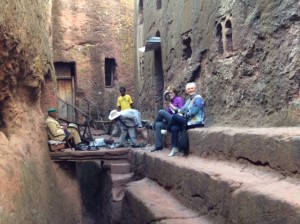

- Ethiopian women outside church in Lalibela celebrating special Coptic religious event

- St. George Coptic church in Lalibela – one of the famous 11th century churches carved into living stone

In terms of racial identity only 40% will have a European background.

The largest church in Ontario is Anabaptist and will project its services electronically into a dozen sites – the pastor has long hair, wears jeans and rides a Harley.

At the same time there will be services in rural Mexico or Pennsylvania where sermons written a couple of centuries ago will be read by men with beards and traditional dress.

Some services will feature bands that would do well in a jazz competition, others will sing soberly to the accompaniment of a Steinway or organ and some will sing A Capella.

The original name for the group now known as Mennonite was Anabaptist. The group originated at the dawn of the Reformation in German-speaking Europe, a world that had been totally Catholic for centuries but was now in religious and social turmoil as groups that would become known as “Protestants” challenged Rome’s legitimacy and authority. The term Anabaptist comes from their practice of re-baptizing adults who had been baptized as infants on the grounds that baptism should be based on freedom of informed choice. This practice of voluntary baptism has since become standard practice in many other Christina groups.

The name Mennonite came from the name of Menno Simons – a converted Catholic priest who provided leadership among the Dutch Mennonites during the early years of persecution. As a result they were called “followers of Menno” by others. It is interesting that even the Swiss adopted this name but the Dutch never did. A translation of their name in Dutch refers to its origins as “inclined to baptize”.

Anabaptist adult members plus associated adherents such as children now number 4,000,000 globally – double the membership of 50 years ago. Many denominations including Mennonites are shrinking in North America and Europe but growing in other parts of the world. Much of the growth represents the more conservative groups with large families and high retention rates in North America plus international churches in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The various Mennonite-related groups in the US collectively represent the largest single national population but Canada has more Mennonites as a proportion of its population. The fastest growing churches are in countries like Ethiopia, the Congo, India, Indonesia and surprisingly Laos.

Mennonites or Anabaptists are a product of the very early Reformation and in all cases took the point of view that neither the church bureaucracy as in Catholicism or the Prince or town authority as in the movements established by Luther and Calvin should determine the belief of its citizens. They were the genuine radicals and free thinkers of the Reformation, promoted separation of church and state and were seen as a threat by all of the other groups. The result was persecution which destroyed much of the original intellectual leadership and forced believers into hiding or migration to less violent locations. The effect was predictable – a radical group shorn of its leadership may resort to efforts to maintain its belief, practices and identity – and in the absence of leadership may become conservative.

The Swiss believers retreated to remote Alpine valleys while Flemish believers such as my family threatened by the rule of Spain and the Inquisition migrated to Danzig and other more liberal Hanseatic locations. Eventually the Swiss believers were physically expelled from Switzerland and were fortunate to have Pennsylvania as an alternative – and became the Mennonites most Americans know. They have enjoyed 3 centuries of mostly peace and a significant degree of isolation.

The other major Mennonite group was Flemish or Dutch and many migrated east to Hanseatic Cities and the Vistula Delta. They experienced moderate liberty (if you exclude all of the wars of those times) until Frederick the Great was unimpressed by their pacifism. Southern Russia became an alternative when the German Czarina Catherine the Great expelled the Ottomans and invited the Mennonites and others to populate and hold the newly conquered lands. That narrative represents my personal story.

The Russian experience was very positive until the catastrophe of WWI and the Bolshevik Revolution. The result was our own version of the holocaust. A portion of the Community had migrated before WWI and others like my family escaped in one way or another during the period of turmoil. These collectively became the other major identifiable group of European Mennonites and are internally known as Russian Mennonites – although the group has very little Slavic blood but did pick up a wonderful cuisine.

The group that remained in the Netherlands prospered during the golden Age of that region and over time integrated with the rest of the Dutch. The group that continues to self-identify as Anabaptist is possibly the most liberal religious group in the Netherlands in terms of social and political attitudes – quite an achievement among the already very liberal Dutch!

Mennonites generally do not have centralized leadership and this creates plenty of opportunity for fragmentation based on differences of theology, dress, geography, language or music. When you align the core theological beliefs they have remained remarkably similar allowing the groups to work together in areas such as social justice or efforts to promote local or global Peace.

Many will recognize the work and reputation of the Mennonite Central Committee supported by most Mennonite Church groups. Leona and I are alumni of that organization and our first assignment related to international social justice was with MCC in Bangladesh after the 1971 Civil War. Others will recognize the work of Mennonite Disaster Service, the retail stores of Ten Thousand Villages or MEDA – Mennonite Economic Development Associates – a pioneer in Microfinance.

WWI created a crisis for Mennonites who at the time were still very rural. Since most were practicing conscientious objectors there was a popular view that Mennonites did not support their nation. MCC was developed out of the wreckage of WWI in 1920 and continues to operate across the world. Many Mennonite churches pioneered in the development of health facilities, senior and mental health programs, mediation and many other social and peace initiatives.

Following WWII the Mennonite Community developed an initiative for young people to model the experience of young men being drafted into the military by developing the PAX Corps as a form of global service. You might note that the name Peace Corps sounds rather similar and is in fact a takeoff from the Mennonite initiative.

The end of colonialism had a dramatic impact on the relationship between the parent churches of North America and Europe and the churches in newly independent post-colonial countries. Outcomes were predictably variable but several national churches celebrated their independence and developed aggressive church growth movements within their ethnic groups or nations.

Mennonites do not have anything approaching a Pope or even a global Synod. We do have an organization with the name Mennonite World Conference which meets every 6 years and is essentially a global celebration of culture and people but does serve to bring disparate groups together through personal interaction. Recent global conferences have taken place in Zimbabwe, Paraguay, Calcutta, Brazil and Pennsylvania. Recent leaders have come from Indonesia, Zimbabwe, America and currently Columbia.

Global dispersion, cultural influence and leadership have pushed various parts of the group in different directions. The horse and buggy Mennonites in Eastern Bolivia or Belize are doing well in terms of economics and numbers but remain very culturally conservative. The Conservative group that moved into the challenging Chaco or Green hell of Paraguay conquered that difficult land and today enjoy an average income 16 times as high per capita as the rest of the Paraguayan population.

Eastern US or Swiss Mennonites have remained challenged by American culture while Western US Mennonites of Russian origin have moved much more into the US mainstream. In Canada the churches and communities include mega-church evangelicals, educated and socially-conscious congregations plus a range of conservative groups that include those who negotiate modernity on their own terms. Some pastors will arrive in church on a buggy and others on a Harley!

Several international Mennonite churches have tended to a charismatic style. Globally, churches will often be mission-oriented but also are known for their work with health, development and social justice.

There is no church requirement to tithe but virtually all Mennonite communities and groups are leaders in the support of various causes. The generosity of Mennonites shows up on Canadian geographic tax donation statistics.

The Mennonite Community has experienced a great deal of group and individual trauma. Virtually all Russian Mennonite families have a personal or family story of persecution, war, dislocation, famine or flight and this leaves its marks. The International churches are dealing with the trauma associated with the post-colonial experience and when I mention countries such as Ethiopia, the Congo, Zimbabwe or Central America no details are necessary. Groups and individuals respond differently and this creates stories where the response to this stress has been very negative – in other cases there are heroic responses.

The point is that any stereotype of the term Mennonite is probably true – but represents a very incomplete picture of the totality of the Community.

Leaders of the various Mennonite groups make efforts to retain the elements of the Mennonite traditions that reflect our uniqueness but more important our contribution to the essence of Christianity. The idea of pacifism or non-violence developed at the earliest stage of our tradition when it was noted that every form of Christian was killing every other kind and justifying the act. The early Anabaptists concluded very quickly that you could not justify the killing of your fellow Christian and that has developed into a comprehensive philosophy of non-violence. This has profound implications for the promotion of Peace and techniques like conflict resolution and mediation. The pacifist stance also has implications for the relationship of Mennonites with their fellow citizens.

Another description of Mennonites has been the term “People of the Book” and the group is very biblically oriented. Mennonites share the view of Jesus as Savior with other denominations but place a greater emphasis (compared to many denominations) on Jesus as teacher and example in terms of community and social justice.

At the practical level this expresses itself through the support of international development, Peace initiatives or work with refugees. Many groups are active in global Missions and others in the local development of new churches. Biblical literalism can also be a cause for division and disagreement.

My personal story is a parallel of our communal experience. The ancestry of my father is Flemish and we can trace our roots back to the Reformation. The family left Catholic territory and became grain merchants in Amsterdam. In 1580 part of the family relocated their enterprise to Danzig or what is today Gdansk. After 200 years of experience ranging from brandy distilling to lace making to becoming an orphan – a member of my family relocated to the Southern Ukraine in 1789 with the first group to accept the invitation of Catherine the Great. The family prospered in Russia and were grain millers when WWI and the Bolshevik Revolution intervened. My father’s family had the foresight to escape to Mexico although it also meant poverty. My father grew up as a shoeshine boy on the streets of Ensenada.

My Mother’s story was similar until the War. Her family stayed and experienced Stalinist repression. Together with two University friends she managed a story-book escape through China in 1931 and all three became Academics in America.

My parents met as refugee children in Russia during WWI and by accident in Minneapolis 20 years later – and then we became a Canadian family. Many Russian-Mennonite families have similar stories of persecution and survival. This family and personal history is part of the reason why I have dedicated much of my life to working with international development, refugees, immigration and Peace issues. Leona did not grow up Mennonite but shares an Eastern European background. Her family was able to emigrate under somewhat more normal circumstances.

My interest and passion for work with development or refugees has undoubtedly been influenced by my exposure to these issues through the Mennonite church and community. The personal experience of family where parents and children were themselves refugees undoubtedly played a role.

The Mennonite Church and Community is diverse. There are many individuals with an engagement and passion that results in the active pursuit of social justice. Others live their lives quietly and like any group of people – some are oblivious to the issues of this world.

To return to the beginning – The Mennonite Community lends itself to certain stereotypes but any one of them is an incomplete picture of this diverse, growing and changing Community.

I was born into a Mennonite home and Community but the decision to remain part of that Community was deliberate. We all live within a tradition or view of the world and I felt that Mennonite values and history were a powerful perspective from which to negotiate life. Leona joined the group through marriage but with conviction and has grown to appreciate the strength of a people and a Community.

The next time you see an opera star at the MET, Premier of a Canadian Province, the CEO of a major corporation or even the Secretary General of NATO, you might ask if they are Mennonite or have Mennonite roots. If you find workers in refugee camps, negotiating Peace or cleaning up after a Disaster – you might find Mennonites among them. Your quiet neighbor or colleague at work may also be a Mennonite.

We are a diverse group but consider ourselves part of the larger Christian family and global citizens. Many find the ethnicity and Community confining and choose a different identity – but Leona and I have chosen to see it as a source of strength. As a Community we share a common desire to live in Peace and to contribute to a better world.