Mia – The Story of a Remarkable Woman (Title of English version of her biography)

This is the title of one of three books (German, English and Russian) describing the life of my mother. She lived through the most tumultuous events and decades of the 20th century and survived with dignity. Born in the reign of the czars she experienced WWI, the Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin, the persecution of Stalin and made a storybook escape to China, later the USA and finally became my Canadian Mother. This is my version of her biography and contains more than a little autobiography. Events often make the person and the story – and that reflects the odyssey of my mother.

—————————————————————-

There are books and movies with plots that are so improbable that they cannot be taken seriously. The story of my mother falls into that category –except that it is completely true! Among other things my mother managed to be blacklisted by the Communist Party in the Soviet Union and later by the Un-American Activities Committee of Senator McCarthy in the USA. Her autobiography is entitled “Mia – The Story of a Remarkable Woman.” This is the story of my mother.

Mother was born on May 9, 1908 in a remote corner of the Russian Empire – within sight of the mighty Caucasian Mountains. Her birth date in early May always presented a bit of a problem since she was born according to the Orthodox calendar and lived the rest of her life under the Julian. She decided to simplify matters by declaring that her birthday would always fall on Mother’s day – a close approximation that assured her of an appropriate celebration and made it easier for the rest of us to remember. This only created a problem in later years when credit card companies and others of that ilk decided to use the birth date of your parent as a test to determine if you are the right person – and more than once I failed that test.

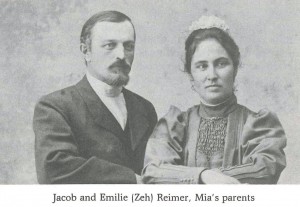

Mother was born prematurely and as an infant with doubtful chances of survival was given the name Mia – the diminutive form of Maria to reflect her tentative hold on life. Her legal name was Maria Jacob Reimer – the masculine second name reflecting the pattern of the time where you were identified with your parent. Her father was a well-established farmer – but that really does not describe the reality of the time or the term. They lived in a prosperous and civilized Mennonite Community that was an island of progress surrounded by the Russian steppe populated with nomads from nearby mountains. Today these former nomads remain in the news as an ideological challenge to modern Russia. Together with his brother Cornelius they owned a large estate reported to be in excess of 10,000 hectares – historical records are sketchy. These brothers and others in the Community were highly competent. Cornelius had travelled to Germany to study horticulture and when I arrived in 1990 the mayor and Community still remembered his property – destroyed in World War II – for its exceptional layout and unique horticultural character. Legend has it that Cornelius and his wife were sent to Siberia as part of the Stalinist purges – presumably for doing things too well. He applied his skill in the underground coal mines somewhere in remote Siberia to grow food for the miners. This brought him enough recognition to be recalled South and given the task of gardener at the dacha of Stalin at Sochi on the Black Sea. He and his wife lived there peacefully until the Nazi invasion when they were relocated to the Far East where they at least died with more dignity than many others.

Cornelius on one occasion was reported to have bred all of the animals and fowl on his farm in white purely for aesthetic reasons. My grandfather reportedly had 40 varieties of cherries on his property and my mother describes his pride in beautiful horses. In light of the tragedies that followed it is difficult to imagine the world of those miniature civilizations and isolated communities. The ‘Colony’ was

composed of two villages with a total population of only 2000 people. One village was on top of a ridge and the other at the bottom. Along the winding road that joined the two villages was a very picturesque ‘aula’ or concert hall where musical events took place. The Community prided itself in education and was known as one of the most advanced of the Mennonite colonies in this respect. This is sometimes difficult to understand in light of the battles about education that were fought within later generations of Mennonites.

Today, as descendants, we are challenged to separate the idyllic stories and memories from the hardship, internal dissension, relationships to the larger society and many other mythological or maybe historical realities. Nevertheless – my mother considered herself to be born into a loving family, a caring and well-established community and church and a comfortable life punctuated by medical and other tragedies that could not be controlled. Whatever the reality of this community – it produced a person of great internal strength and outstanding character and values.

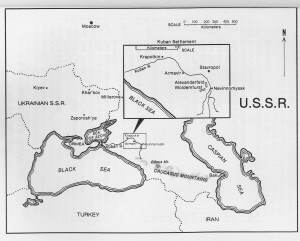

My grandfather was a direct descendant of part of the family that provided the leadership in a split within the Russian Mennonite Church in 1860 based on pietist influences from Germany. The (ethnic Mennonite) Community and Church had become largely indistinguishable and this created the opportunity to again remind the group of its origins where personal faith and appropriate lifestyle played a greater role. This was not well received by those in power and the new group known as Mennonite Brethren experienced many challenges resulting in 65 families relocating from the comfortable and well-established villages of Central Ukraine to the newly pacified steppe at the foot of the Caucasian  Mountains. Between the challenges of changes in climate and soil and marauding neighbors – it was not an easy beginning but the Community eventually became established and very successful. Vineyards represented the first commercial agricultural success and carried the community in its early years. This was a bit of a contradiction in view of the strict abstinence of the new religious tradition.

Mountains. Between the challenges of changes in climate and soil and marauding neighbors – it was not an easy beginning but the Community eventually became established and very successful. Vineyards represented the first commercial agricultural success and carried the community in its early years. This was a bit of a contradiction in view of the strict abstinence of the new religious tradition.

Decades later I would attend a banquet in the same region in a Resort used by Kremlin leaders on vacation. As the mayor, inebriated before dinner even started, plied us simultaneously with beer, cognac and vodka I was having trouble keeping up. The old stories about vineyards came to mind and by now the Caucasus had become famous for its wines and champagnes. I reminded him of the tradition of my ancestors and somehow thought a switch to wine might help me survive the evening. With great gusto he stopped the whole process – someone produced six different varieties of local wines and we were required to taste each one of them before we got back to the hard stuff – and his idea of tasting wine meant a full glass!

My maternal grandmother was always somewhat of an enigma. Her picture shows a regal and confident person with black hair and eyes and reportedly with olive-colored skin. Clearly her ancestors had not made the traditional Mennonite trek from somewhere in the Lowlands of Northern Europe through Prussia into Russia. She was Emilie Zeh – the name taken from her adoptive German parents from the Crimea. Since the Crimean locals could be expected to be Tatars or Mongolian in origin and given her adoptive status I always suspected she was at least partially of that heritage. The recent advances in DNA analysis have allowed me to test that hypothesis and I do admit to some disappointment that Genghis Khan or one of his lesser nobles do not appear to be part of my ancestry. On the other hand the DNA suggests that Ashkenazi Jews, Berbers from Tunisia, a population in Bosnia and strands from Gypsies and others all figure somewhere in her makeup. That combination of parents and history produced the person who is my mother and somehow I have to believe that this mix of genetics and tradition contributed to her unusual personal strength and character.

The remote location of my Mother’s village at the extremity of the Russian Empire reminds me of the story of Dr. Zhivago. As World War I ended to be followed by the various manifestations of civil war, local brigands (celebrated by others as nationalist heroes) and finally the Communist Revolution merged into one forgettable blur. However, some remote parts of the empire carried on with minimal disturbance. When these internal battles ended to be replaced by the official oppression of the emerging Communist dictatorship – reality finally struck. My grandfather, as a community leader, left his f amily and participated in the organization of the famous escape of many Mennonites from Moscow by rail through the Red Gate to Latvia and then wherever they could find a place in the West. He planned for his family to join the exodus as time and politics closed in – placed his name on a list for a future train and went to the deep South to collect his family. Tragically, another person replaced the name of my grandfather with his own – and placed our family on a later train that never left Russia. He went into hiding and after a number of years the Communists caught up with him and together with the elegant Emilie they lived out their days in a remote village in Siberia.

amily and participated in the organization of the famous escape of many Mennonites from Moscow by rail through the Red Gate to Latvia and then wherever they could find a place in the West. He planned for his family to join the exodus as time and politics closed in – placed his name on a list for a future train and went to the deep South to collect his family. Tragically, another person replaced the name of my grandfather with his own – and placed our family on a later train that never left Russia. He went into hiding and after a number of years the Communists caught up with him and together with the elegant Emilie they lived out their days in a remote village in Siberia.

The stories of escape or tragedy have an incredibly random character to them. My paternal grandfather made the same journey a number of years earlier. The family myth is that at the time of departure authorities called out the names of people they wanted to exclude from the exodus – and called my grandfather’s name. They had one of his initials wrong – all Mennonites or at least all DeFehrs were known by their multiple initials. It seems that one initial was incorrect and my grandfather convinced the official that it must be a different person and escaped to the West. The journey took them to Latvia, Germany, France, Spain, Cuba and finally Mexico. They were denied entry to Canada at that moment because of the trachoma of the very aged grandmother. As a result my father would spend some of his teen years on the streets of Ensenada in Baja California shining the shoes of American tourists.

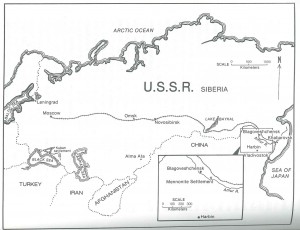

My mother decided to enter medical studies in the new Soviet Union. As the ideological noose of Stalin closed in on her world she was called in front of a student assembly to renounce her (kulak) parents and her Christian faith. She and two friends would do neither and they were banned from all further study in the Soviet paradise. They left their families and went underground in Moscow where Mia had a sister working in the Embassy of Finland who provided access to food coupons. That kept them alive for the winter while they considered their diminishing options. The borders to the West and South had become impenetrable – but there were rumors that people were escaping through China. May Day of 1930 the three young women attended the infamous military parade in Red Square and impulsively joined a marching parade of “joyous workers of the Soviet Revolution”. They walked in front of Stalin and as they emerged on the other side of the square managed a quick exit into the crowd before they were apprehended. May 2 they departed on the legendary Trans-Siberian railroad to the Far East of Siberia. They were aware of some Mennonite communities in the region so went to the local market to listen for accents and voices. They located some low-German Mennonites who hid them in their empty wagons and took them back to hide in their village near the Amur River that bordered Manchuria. Escape was not easy but escapes were taking place in small groups across the river with the help of Chinese human smugglers.

On the appointed day the young women joined a small group that made their way to an island in the river – only to discover that the Chinese “coyotes” did not arrive. They hid among the sand dunes and survived on the island in spite of Soviet guards. 24 hours later they made the crossing with the help of a small raft for people like Mia who could not swim. During the crossing one of the Chinese guides panicked and climbed onto the raft which promptly capsized. My mother was in deep trouble and another young man with the last name of Copper rescued her – years later I was able to visit him in a village in Paraguay and offered him my gratitude.

Arrival on the Chinese side of the Amur was not an occasion marked by any papers or official action – they were in one of the most remote corners of China after the end of Empire and before the Japanese invasion – they were on their own. A Russian woman married to a Chinese man approached them on arrival and suggested that staying this close to the border was very dangerous – the “guides” were perfectly capable of earning their fees a second time by selling them back to the Communists. Taking her advice they left their local hostel where they shared a sleeping platform with half of China and walked into China in the middle of the night. The Russian woman was waiting for them at the edge of town with a package of food and her blessing and these three twenty-something young women walked into the Chinese night.

The next part of the story always remained a little vague in their various biographies. My mother did acknowledge (verbally but not in her autobiography) that at one point they were taken or captured by a local Chinese leader of undetermined local power who claimed that since they were unattached they would be his concubines. The story goes on that some of the Russian Mennonite young men on a parallel personal journey who heard of this misadventure approached the Chinese man and advised him that he had captured their wives – and as a “person of honor” they were released and continued their journey. When their captor asked if they were married they apparently pointed wordlessly at the young men who had heard of their predicament and who had arrived to claim them. Mia told us that it was as close as she ever came to a lie! Who knows the truth – something happened that they chose not to write about or at least limit the truth.

There were in fact three counterpart young men who had participated in the plans to escape during the winter in Moscow. In the end they had felt that taking three young women with them would be too dangerous and complicating and had ventured on their own – leaving their girlfriends behind. It happened that the men had a much more harrowing journey and on their eventual arrival in Harbin – the destination of every escapee – they were in terrible shape and were nursed back to health by the young women they had abandoned. Tragically – one of the couples decided to marry in China but the groom became sick on the wedding day and died within days.

The women eventually managed to take one of the river boats that traversed the Amur and then up the Sungari to Harbin where they joined the eclectic “White Russian” community of refugees of every stripe. The ship had to use parts of the Amur river that were in Russia to avoid the sand bars so the women were rather nervous until the ship finally turned south and deeper into China! They reportedly hid in the cargo hold during the times when the ship ventured into Russian waters. In Harbin they worked as nurses to the arriving refugees while they considered the next move. They could not be aware that they were within months of the invasion of Manchuria by Japan.

Many groups complain of discrimination during this period in that they were denied entry by Western countries – but this was an almost universal condition. The only destination available to the Mennonite refugees accumulating in Harbin, Manchuria was the Chaco (green hell) of Paraguay. A group of conservative Mennonites had left Canada a few years earlier and had settled in the very heart of this desolate place that had resisted all attempts at settlement by Europeans for centuries. Conditions were challenging, the death rate was high and if they emigrated there they would face a grim future of working in the fields to carve a living out of this desolation. They decided that they had not risked so much to become farming pioneers in such a desolate and intellectually sterile place and planned a more daring adventure. They took a boat to Yokohama in Japan and then a ship to San Francisco – without any papers whatsoever. On arrival they were predictably interned on Angel Island – the immigrant counterpart of Alcatraz in the same Bay. Fortunately a man from the Salvation Army was regularly scouring this immigrant prison to see what kind of human flotsam might be washing ashore. He sensed that these women might have a future given their abilities and youth if he could find a place in some College or University. He managed to arrange a

scholarship at Bethel College in Minneapolis and that allowed them to enter the United States after a couple of harrowing years on the road. After a short time the Mennonite Colleges in Central Kansas heard the story and suggested that they could “take care of their own” and invited the young women to Kansas where they each earned their first degree. All three went on to graduate degrees and all of them became university professors. My mother earned her third degree at the University of Minnesota and became a professor of German literature.

I was to grow up us as a child listening to the usual German fairy tales punctuated with an appropriate amount of Schiller and Goethe. I was raised in a community where our neighbors shared this (German-speaking Russian Mennonite) heritage and that resulted in a Kindergarten operated completely in German – as was our local congregation. Our teacher ‘Tante Anna’ had been educated in Berlin before the revolution and had all of the competence and discipline we associate with the educational tradition of Frederick the Great. She had not been told that 5 year-olds could not read or write so we were taught to read and write German – but she used the Gothic script! As a result our class of Kindergarten grads was later accommodated by the local public school in that we had a special class and teacher who taught us in German and in Gothic until Christmas – then we made the transition to the English language and the Latin script. This was taking multiculturalism to an extreme!

Mother survived initially through the charity of Colleges and friends and managed to support her parents in Siberia during years when contact was still possible. This ended with the purges of 1937-38. She had a compelling personal story and was asked by churches, service clubs and University-arranged audiences to share her story – which would result in a gift of cash or in kind. This allowed her to complete University and provide parental support – in the middle of the Great Depression! The University would arrange her speaking tours – she told us that she had accumulated news clippings of about 500 presentations – many to Russian-interest groups. This was to haunt her after she emigrated

to Canada to marry my father. US immigration reportedly kept her album of news clippings. In 1952 when the young family had stabilized we made our first trip as tourists to the USA. On arriving at the border they asked about her background since she had been placed on some version of the famous or infamous “Un-American” list. Whoever had scanned her clippings had not been able to distinguish the difference between talking about her dramatic escape from Communism to supporting Communism. The record was finally cleared in 1956 and our family could enjoy all of North America. My mother had actually been an American citizen but was never bitter about this part of her treatment by US authorities – she remained grateful for the haven and the opportunity of her arrival from China.

A decade later I would enter the US for University studies. These were the sixties – a time of idealism and transition and a great time to be a student. After marching with Martin Luther King on the epic Selma-Montgomery adventure and participating in many anti-war or anti-violence events I managed to attract the attention of the FBI. This resulted in the loss of my security clearance in Canada and with that the loss of my appointment to the Canadian Diplomatic Service. My mother was actually rather proud of the fact that at least my values were noticed! She was rather inventive in these kind of situations. During the thirties she would frequently travel to Canada to visit her brother and sister. Returning to the USA the border authorities would ask “where were you born” and with Russia as the answer this always caused a long discussion. Since her home was technically in the area that had once been Northern Georgia – my mother reverted to saying “Georgia” when asked that question and that made entry a lot simpler!

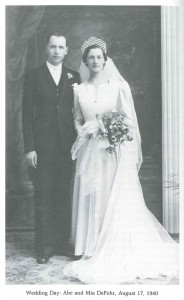

Mother had several opportunities to marry educated Americans but somehow felt that she wanted to live closer to the kind of community she had known in her youth. With the outbreak of WWII American University authorities had the brilliant idea that closing German Departments would somehow aid the war effort and she lost her appointment. She decided on further studies and at that point met my father. His family had reached Canada via Mexico in 1924 and as a poor immigrant he managed to learn English and complete Grade 11. In 1939 he was traveling alone by car from Winnipeg to the New York World’s Fair and stopped for night at friends in Minneapolis. It was a Sunday and his hosts were aware of several German-speaking women at church and invited them for Sunday lunch. It happens that my father’s family lived well to the north and was in relatively greater distress during the years of the Bolshevik Revolution and Civil War and the entire DeFehr family had found refuge for two winters in the village of my mother. Although she was two years his senior they had met as children and now their paths would cross as a random event on the opposite side of the world. My father had traversed Europe, the Atlantic and Mexico to Canada and mother had traversed Siberia, China and the Pacific to the USA – now they would meet in a manner that can only be considered as destiny!

Mia was a person of strong character and discipline. She had spent a decade where she had experienced intellectual challenge and had participated fully in modern society. She drove a car, wore lipstick and attended movies – all of which were frowned upon in the conservative immigrant community she joined by marrying my father. She had made a choice to live in community and managed to refuse to be dominated by these restrictions although she lived within them. Mother was leader of a group of younger women in her church and helped them with the social and intellectual transition to a larger world. Eventually the church closed down her ‘radical’ class but participants of that group to this day talk to me about mother and the impact of that class. Years later I would receive a large coffee table book about the work and life of Gathie Falk – a significant Canadian artist. In her biography is a picture of mother and her group of girls – including the artist. She refers to mother as “a proto-feminist and important mentor. DeFehr was a woman of extraordinary character and education….” Whatever Mia was – she was ahead of her time. Two decades later I would lead a Sunday School class with a colleague and we found the affairs of the world (rather than the prescribed curriculum) more interesting and in our view more useful to the students who chose to attend. Somehow the congregational authorities of that later time also found it in their wisdom to shut down this class and invite attendees to spiritually safer venues – regrettably the majority stopped attending both the class and our congregation.

The community that Mia entered might have been intellectually restrictive but somehow the world of my mother always remained global. It is rather common today for “Mennonite” authors to write about the incredibly conservative and stultifying conditions under which they were raised. Somehow they became Ph.D’s and authors in spite of these limitations. It makes for good novels if you have talent – but the Mennonite communities were no different than the immigrant communities of every other tradition – but tell that to an author who is winning honors for mining a subject that is already history! Mother loved gardening and nature but housework was considered a regrettable necessity – she did it dutifully and well but had refined it to an art-form. She had a 14-day menu with practical and tasteful meals that were faithfully reproduced on schedule. This allowed for maximum planning and minimal effort to produce the needful. This created time and space for intellectual intercourse with a great variety of neighbors, friends and correspondence. Mother stated that she maintained contact through letters with 300 people around the world. She would serve us lunch (we walked to and from school and returned home for lunch – winter or summer) and then took the afternoon to write – every day! Somehow every missionary or President of a Mennonite College who passed through town spent time at her table and the intellectual debates were lively.

We were raised with compassion and support but with high expectations. There were two plaques on the wall of our kitchen. The plaque placed by my father read “Aim Higher Than You Can Reach” and the plaque of my mother read “It Matters Not How Long You Live But How I” If praise was appropriate it would be given – but school came easily to me and her comments reflected that reality. I might come home with the highest grade in class but if it was a result of less than maximum effort she would simply say – “You can do better”. Mother would plant a garden and then phone the University and have long discussions about the scientific merit of particular plants or the care of them. She engaged fully in the social life and the caring community of support around her – but led what seems like a complete double life of books, correspondence, friendship and travel.

Some people think that I travel a lot and I do. However, I was well into my fourties before I exceeded the number of countries visited compared to my mother – and she lived in an age where there only half as many official countries on the map! She was completely satisfied living in her community – helping her neighbors and friends to grow and develop and make her personal mark on the neighborhood and the world. Anyone who met her remembered her vividly. There is a story about two men who did know each other sitting on a flight in Business class and somehow the conversation turned to me and one person stated that “You should meet Art DeFehr!” The immediate riposte from the other person was – “You should meet his mother”.

Mother felt a responsibility to the larger world although limited by family obligations and the reality of the time. Although the immigrant community was financially very constrained the women managed to collect and prepare all manner of supplies and services to refugees around the world and the needy closer to home. I have this strange memory of a teepee pitched in our backyard one winter. Presumably it was an aboriginal man who was spending the winter in Winnipeg and somehow our family managed to provide some manner of support. When refugees from WWII began to arrive in Canada our home together with many others in our relatively poor community hosted these families. The Mennonite church has organizations that are oriented to proselytizing and others, especially the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) that provide services related to war, poverty, development or human rights. These agencies are very specific about their turf but in my upbringing they merged into one – I did not appreciate the difference between missions and service to the world until I arrived in University. This inability to separate the larger mission of the church into its component parts has caused me a great deal of trouble since I still see the total mission of the church as part of a whole.

Every child presents unique challenges to a parent and I presume that I was no different. Mother was influenced by her education and would call the University for advice and when in doubt we were raised by Dr. Spock. His later apology to the world was of little benefit to me where it may have been inappropriate. Hindsight suggests that I was a restless child and she searched for ways to keep me challenged. At age 14 I was sent to camp as a part of the staff to work in the bush and maintenance rather than be a camper. At age 16 I wanted to work at Banff for the summer and she rather found me another Christian camp at an even greater distance.

Given her own experiences as part of a much larger world in the thirties she could not be convincing about a restrictive view of life and reality. Instead of too many rules and boundaries we were told that we could and should use our own judgment about how we spent our time and what events we attended – but she had a very simple but effective rule. When we came home we were obliged to tell her all about our experiences – if we were embarrassed to tell her we probably should not have been there.

University was an intellectually challenging and liberating experience for me – as it had been for my mother. I was very conscious of her attainment under much more difficult circumstances and was determined to at least match her accomplishments. I graduated with two Bachelors degrees and then went on to an MBA at Harvard. Both my mother and I found the experience of that grad very meaningful and I felt liberated from that personal burden.

In 1972 I was asked to become the Director of the new Bangladesh MCC program following the end of the civil war. When I received the invitation I indicated that given my role in the family business I would need to check with my parents first. The person making the phone call happened to my first cousin and he simply replied – I already checked with your mother and she simply stated that it was time for Art and Leona to go and do something in the world. Mother had a very clear sense of what was important in her life and the life of her children.

Mother had married into a community but also the personal situation of my father. As an immigrant and with the completion of Grade 11 during the Depression years, his opportunities in life were limited. He worked for Piggly-Wiggly, the San Francisco predecessor of Safeway. He was very proud of the fact that he introduced better methods of caring for the display of fruit and vegetables that made them more attractive – an idea that was then applied by the company more broadly. This success notwithstanding, in the early thirties he was summarily fired. On asking for the reason he was advised that they were following instructions from HQ that when a person reached the top of the wage scale that person should be fired and replaced by a person at the bottom of the scale. They advised my father that he was an outstanding employee and they would be pleased to hire him on Monday as a new employee at the bottom of the scale. This happened to my father 3 times during the thirties. When my father searched for employment after WWII my mother encouraged him to work on his own rather than risk being humiliated again – and stated that “she would live on whatever his income would be.” During the early years of marriage she dutifully and effectively sewed clothing, managed an incredible garden, prepared many items of food for winter, raised chickens and ducks and stretched the income of my father.

In 1944 my father started a wood-products business that was to become the largest manufacturer of furniture in Canada and the largest private employer in Manitoba. Mythology has it that he sold his car for $500, purchased some equipment that was installed in our basement and began to produce whatever the market would accept. I recall our living room as a kiln dry for lumber and our garage filled with finished product. Mother was never directly involved in the business but was certainly aware and supportive.

Mother’ sense of service to the community extended to her style of philanthropy. When my father returned with his weekly salary during the first years of marriage – the first 10% of his $22.00 per week salary went into a milk jar that would later be dispersed as donations. She supported many different ministries but always had a special place in her heart for students. When mother wanted to repay some of the charity directed toward her as a student one benefactor told her to “gib die liebe weiter – pass the love along.” She always felt that her debts had not been adequately repaid and many students received lodging, funds or encouragement to help them achieve some particular educational goal. When mother died she had arranged for the security of several relatives in challenging situations, left a small legacy for each grandchild and beyond that her estate did not really exist. She had managed to disperse all available funds under her direction before she died.

One particular anecdote speaks to her tenacity and her influence in the community. On the way to church from our home – mother always walked – lived a family with nine children of whom the majority were mentally challenged and had parents with limitations. The house, yard and care of children reflected these realities. Mother was distressed and decided that the family really needed a larger home – fortunately they lived on a rather generously sized property. She went to the local lumber yard to have a plan drawn that doubled the size of the house – then went to every contractor of relevant services to assign him his part of the project. She would then add that they should not bother to send a bill to anyone. One of these contractors recalled years later that it was much easier to perform the job gratis than argue with Mia.

In May of 1971 at the age of 63 mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. Surgery followed but the cancer never left her. She lived these final years with dignity and people who came to offer sympathy

often felt encouraged instead. She used these years to spend time with her children and grandchildren and managed to write what would become the essence of her biography. These notes have been taken by three different authors and resulted in an initial book written in German, a second in English and later a novel based on the story written in Russian. Many have been blessed and encouraged by her story.

Many anecdotes could be added but she was a person who navigated a place in time and history that absorbed and destroyed millions around her. She accepted the limitations of her place in the world but also took full advantage of every opportunity. As I watch my own life unfold and my own response to challenges and opportunities I can often recognize the legacy of my mother. She left a great personal legacy – a remarkable person and a remarkable life.

Mother died surrounded by a loving family in June of 1976 at the age of 69.